Here,

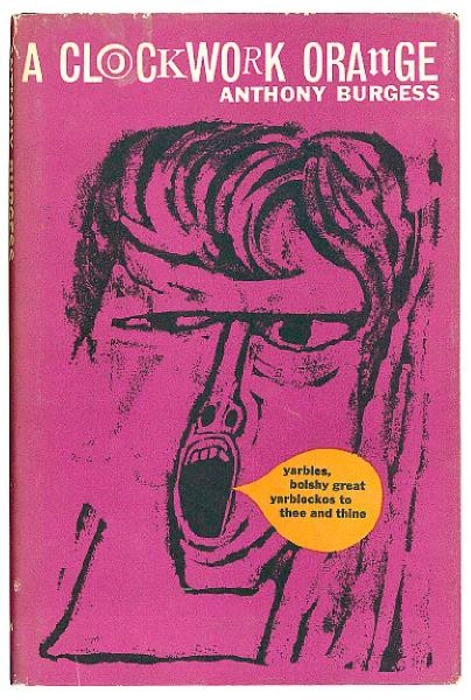

I here republish the first book I completed in Hundred Book Challenge

originally published here on

May 28, 2013.

What’s it going to be then, eh?

This 1962 novella by prolific British

writer Anthony Burgess reads like a bead of water skittering across a

hot skillet.

The story follows our “faithful

narrator” Alex, a 15-year old-gang leader in a vaguely futuristic

and dystopian England. Alex first shows readers a life of crime and

debauchery followed by being institutionalized and “rehabilitated”

by an oppressive government using nightmarish methods to force Alex

to associate criminal behavior with physical sickness- a method that

works, forcing Alex to do good to people rather than evil. The

opposition to the government then attempts to use Alex as a poster

boy for government gone wrong, ultimately sending him on a suicidal

jump out a window before being reverted back to his previous, violent

ways by the government afraid he would become a martyr against the

establishment. The final chapter, excluded from U.S. publications of

the book and the Stanly Kubric movie, shows Alex as a more mature 18

year old growing tired of crime and violence and thinking about the

future of a wife and child.

Much has been said and written about

the story thanks mostly to Kubric’s movie adaptation. I saw the

movie years before I read the book and I have to say the book is a

more beautiful creation using the invented slang called Nadsat to

punch around the more violent and awful portions of the story- of

which there are many- as opposed to the movie’s stark images of

nudity and violence. The violence and disturbing scenes are still

there, it’s just done so in a way where the character of Alex is

highlighted rather than the shock of seeing the violence happen under

bright, harsh lights.

Bringing beauty to the violent and

horrible seems to be an early theme in the 100 book challenge’s

early entries as I chose, by complete random selection, to listen to

“A Clockwork Orange” at the same time as reading “Lolita.”

Anyway, much has been said. I didn’t

find myself at any point rooting for the future of young Alex who

seemed aloof to the whole situation. Instead I found myself riveted

by concepts of leadership and government.

At no point is any form of leadership

given in a positive light. Alex’s trouble starts because he tries

to force his leadership on his small gang. Both the government and

the opposition try to force Alex to their side- or rather try to

force Alex’s condition to their side.

Yeah, we never see that sort of thing

now, right? Natural disasters, murders and huge news stories aren’t

commandeered by opposing political or social forces causing the

humans involved to lose their humanity.

Indeed the government seems to be to

blame for the packs of wild youth terrorizing the world by night in

the book. Alex points out that the only question asked by authority

is why do kids act bad, never why do they act good.

The point being the need for free will

is paramount to all other needs. Safety, security and all other

options are secondary to free will. As the prison chaplain said in

response to Alex’s treatment:

“What

does God want? Does God want goodness or the choice of goodness? Is a

man who chooses the bad perhaps in some way better than a man who has

the good imposed upon him?”

Or, as Alex says several times:

“What’s

it going to be then, eh?”

The final chapter seems a bit at odds

with the rest of the book. The supposed message being that violence

and control is something you grow out of. Burgess comes right out and

says that’s his point and his view on the purpose of a novel.

Without any sort of change in character it’s not a proper novel,

Burgess says, but rather a fable. Of course, it doesn’t jive with

the rest of the story where you see adults working for the government

still in the thrall of violence. Alex describes a teenager as a

wind-up toy that looks like a real person but only travels straight

ahead bumping into things as it goes. It’s given as an unavoidable

that teenagers will want nothing more than to rape and pillage

through life and then become sensible as adults. Again, this doesn’t

seem to be a realistic approach in real life or the fiction Burgess

created.

Two things:

First, there is no such thing as a

clockwork orange. The image is supposed to create a sense of a fake

human- something as fresh and juicy as an orange but with nothing

real inside. It’s the title of a fake book within the novel that

seeks to change the government from such totalitarianism- arguing

that people who are controlled all the time are as lifeless as a

clockwork orange.

Second, if at all possible, listen to

the audio book version like I did thanks to the advice of my friend

Mary Einfeldt. Not only is it probably the easiest way to approach

the thick Nadsat slang, it’s also a pretty wonderful performance.

No comments:

Post a Comment